AN ESSAY ABOUT HOW BIG LIFE WAS STARTED, BY NICK BRANDT

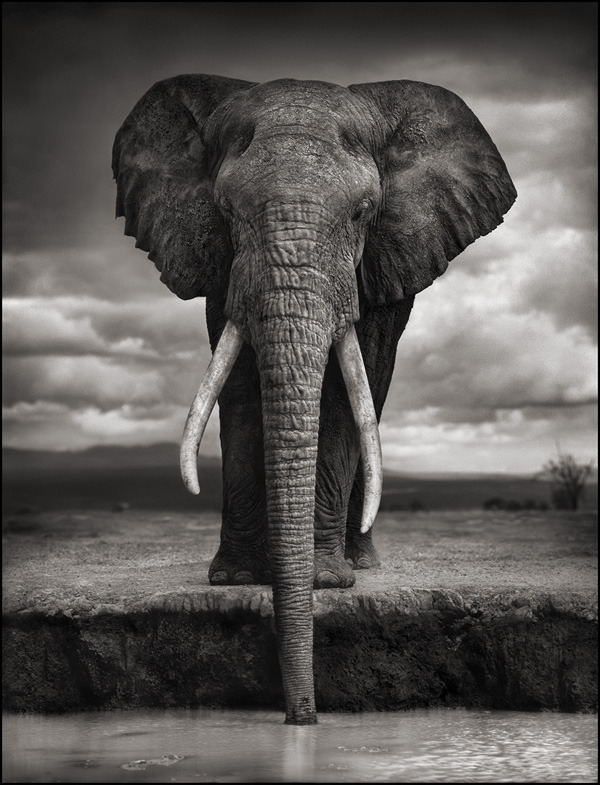

Elephant Drinking, Amboseli 2007. Killed by Poachers, 2009 by Nick Brandt

2009-2010: Dark Days in Amboseli

Back in June 2010, I would never have imagined that I would be writing this - about how I began a Foundation to help protect the animals and wild lands of East Africa. It was one particular trip that started the whole thing:

In July 2010, I returned to Amboseli National Park in Kenya, one of the photographic locations for the third book in my trilogy, for the first time in two years. Over the previous eight years, I had spent many months photographing many of the elephants that live in Amboseli. As a result, I had been fortunate to know these elephants and their habits intimately.

But what I witnessed during that trip was very different to those in earlier years.

On the western side of the park, day after day, I tried to approach what had once been a few of the most relaxed of elephant herds, elephants that in the past quietly made their daily journey to the swamps, moving right past the vehicle without a care in the world. But this time, within half a mile of us approaching them, they would now run in terrified panic. Meanwhile, gunshots were being reported from the direction the elephants came, near the Tanzanian border.

I tried reporting what we’d seen, telling the authorities where to look, but nothing was done, nothing happened. The Kenya Willdife Service was/is underfunded, there were almost no NGO's in the area, and those that were there had almost no money at all. And on the Tanzanian side, there was no-one at all to talk to.

It was quite shocking to discover this situation here in Amboseli, one of the most important and famous ecosystems in Africa, and with the most spectacular remaining population of elephants to be seen in East Africa, in fact, in my opinion on the whole continent.

Whilst there, I also discovered that 49-year-old Igor (as named by Cynthia Moss of Amboseli Elephant Research), the elephant in my Elephant Drinking photo above, had been killed the year before. As had Marianna, the matriarch leading her herd boldly and purposefully in the photograph below.

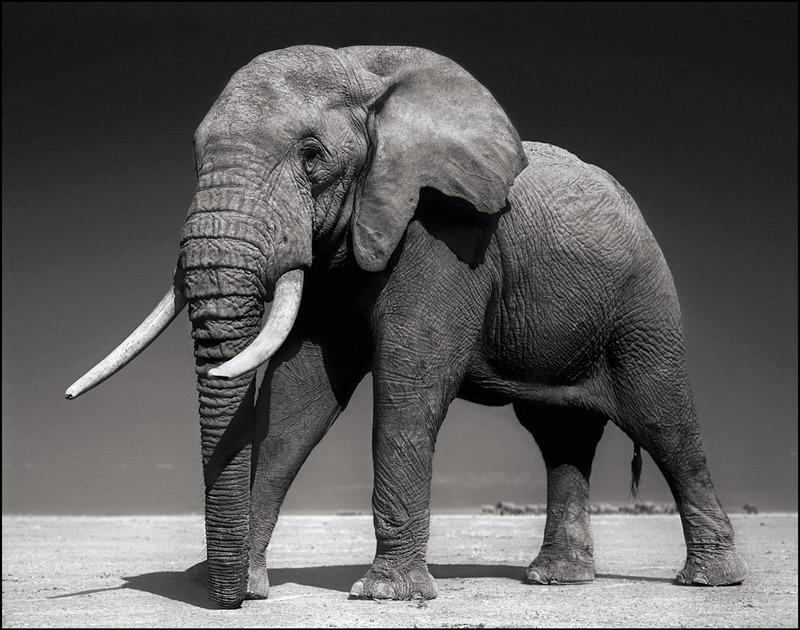

Elephants Walking Through Grass, Amboseli 2008. Leading Matriarch Killed By Poachers, 2009

Elephants Walking Through Grass, Amboseli 2008. Leading Matriarch Killed By Poachers, 2009

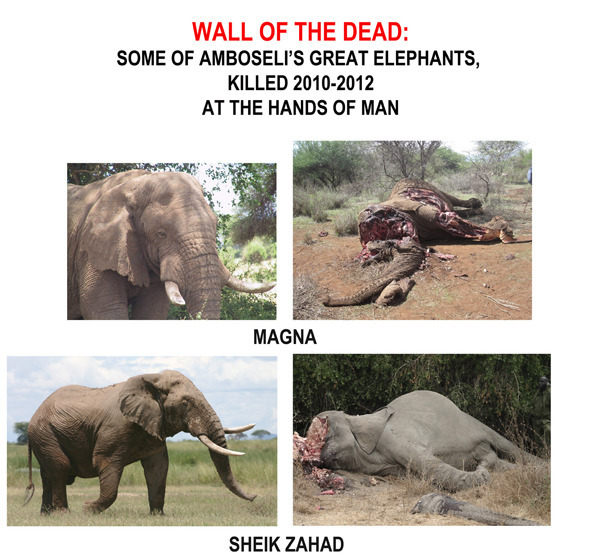

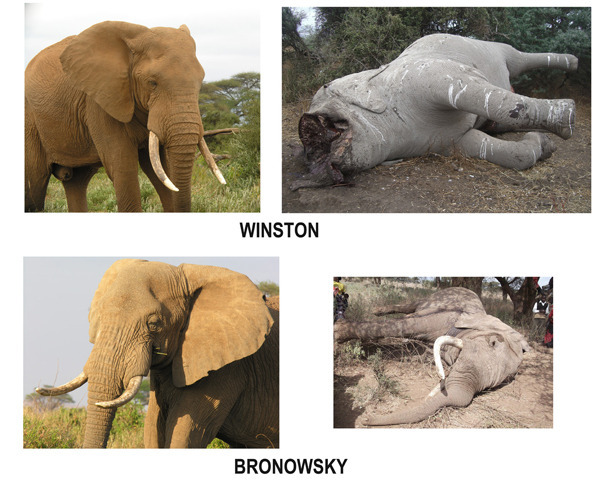

Over the coming weeks, there was a lot of bad news. Just six weeks after I took the photo below of Winston, this 30-year-old elephant was shot by poachers over the border in Tanzania. Wounded, he made it back over to Kenya, but then died, and also had his tusks sawn off with a power saw by the poachers.

Elephant with Half-Ear, Amboseli, July 2010. Killed by Poachers August 2010

Elephant with Half-Ear, Amboseli, July 2010. Killed by Poachers August 2010

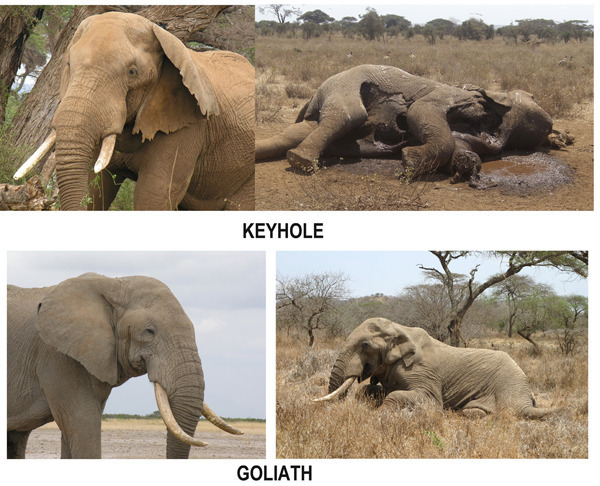

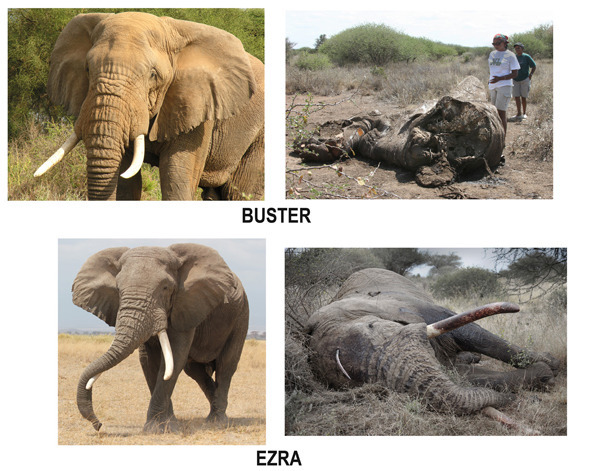

Over the rest of the year, the roll call of big bull elephants killed by poachers came thick and fast: Goliath, Sheik Zahad, Keyhole, Magna. About ten in total that were confirmed as killed for their ivory. It wasn't just a case of IF an elephant was going to get killed, but WHEN.

At first I thought the poachers would just target the elephants with big tusks. But elephants with tusks barely more than broken stumps were being killed by poachers. Which means that really, no elephant was safe any more.

Escalation of Poaching Across Africa & In the Amboseli Ecosystem

Since 2008, the poaching of animals, most of all elephants, had dramatically escalated across much of Africa. There has been a massively increased demand from China and the Far East again, ivory prices have soared from $200 a pound in 2004 to more than $2000 a pound today. Some experts estimate that as much as 35,000 elephants a year are being slaughtered, 10% of Africa's elephant population each year alone.

Some of the methods being used are frighteningly simple - from concealed poisoned spikes that pierce the elephants’ feet, to poisoned melons and pineapples, all of which kill the elephants in unimaginable pain.

But the killing is not limited to elephants. Lions are being killed at an incredible rate too. There are just an estimated 20,000 lions left in Africa today. That’s a staggering 75% drop in 20 years. Most of this is due to conflict with the fast growing population. But increasingly, it is for body parts, again for the Asian market, now that tigers are too hard to procure. It has become so bad that there are next to no lions left outside the parks and reserves.

The plains animals are getting slaughtered as well: Giraffes here in the region are being killed at a faster rate for bush meat. There are even contracts out on zebras, as their skins are the latest fad in Asia.

The Amboseli Ecosystem, 2010: No-One to Fight Back

Initially, the notion of starting my own Foundation to address this problem seemed self-aggrandising to say the least. But I saw the destruction unfolding before my eyes - not just the elephants and lions, but also the giraffes, zebras, gazelles for bushmeat - with almost no real effective or meaningful protection for this incredible ecosystem. And I thought I can’t just do nothing. It’s no good being angry and passive. You have to be angry and active.

One of the most obvious things - you don't need to major in philanthropy to figure this one out - was that many NGO's don't actually have key leaders on the ground in far-flung project areas coordinating, supervising, overseeing the projects. They try and run their various projects from a desk in Nairobi or worse, from London or New York or Washington.

But in my opinion, you have to have your leader on the ground, in situ, to see, direct and co-ordinate operations firsthand, to marshall resources with the other groups there, to have an open door and open ear to the local community. If you don't have the local community on your side, you're screwed. For exchange of information, the bush network beats Facebook any day. In the bush network, everyone knows everything what is going on.

Also most of the poaching in Kenya was being done by poachers coming over the border from Tanzania. The Tanzanian side has already been massively denuded of wildlife, and there were literally no authorities or NGO’s there to stop them anyway. So the poachers would come over the border from Tanzania, make their kills and escape unimpeded back to the safety of Tanzania.

Clearly what was needed was teams of rangers on both sides of the borders, working in close communication, so the rangers in Kenya could radio those on the Tanzanian side, to track and pick up any poachers crossing back over into Tanzania. Again very obvious, but no-one was doing this. A trans-border anti-poaching operation was desperately needed that would be the first of its kind in East Africa.

And then finally, the few rangers that there were mostly were on foot, no vehicles to effectively patrol and give chase, and without the necessary basic equipment: cameras, GPS’es, often even without radios. They needed to be mobile, and they needed to be able to communicate.

October 2010 - Big Life Into Action

After consultations with the Kenya Wildlife Service, who welcomed our intervention into areas of the ecosystem that they were not covering, I called renowned Kenyan conservationist Richard Bonham. He lived in the adjoining area of the Chyulu Hills, and had started the Maasailand Preservation Trust 18 years earlier in that area, with teams of anti-poaching rangers situated there. I told him my ideas and asked him if he knew anyone I could hire.

He said that he had been shouting everything I was saying from the treetops for years, but he never had the funds to implement. At that moment, we agreed to join forces. He became Director of Operations for Big Life Foundation.

At the same time, I had contacted Damian Bell, who founded the Honeyguide Foundation in Tanzania, that specifically concentrated on the confluence of conservation and community. No-one in Tanzania had better working relationships with the local communities in this regard than Damian. He became Projects Manager for Big Life Foundation in Tanzania.

With those two experienced, talented individuals on board, we were set to go. I was very, very lucky to have both men on board the team from the very beginning.

We also were sure to gain the support and co-operation of the Kenya Wildlife Service and the local communities on both the Kenyan and Tanzanian sides, without whom it would be impossible to operate effectively.

With the extraordinary generosity of Fiona and Stanley Druckenmiller in New York, and Stan and Kristine Baty in Seattle, amongst the most devoted collectors of my photos, we were given enough funds to start implementing a significant initial infrastructure that reaped almost instant results.

Five months later, we had:

Constructed and expanded twelve anti-poaching outposts, each staffed by eight rangers; purchased nine anti-poaching patrol vehicles; recruited platoon commanders and a training instructor to oversee eighty-five fully-equipped rangers; purchased a Microlight plane for aerial monitoring in Tanzania; acquired two sets of fully-trained tracker dogs for both sides of the border; and massively expanded our informer network on both sides of the border.

With that, we quickly achieved things in the last few months that the authorities had not managed for two decades. Within three months of being established, Big Life succeeded in the major coup of breaking up the worst of the three main poaching gangs operating along the Amboseli region Kenya/Tanzania border.

As of September 2012, this new level of coordinated protection for the ecosystem has brought about a major, dramatic reduction in poaching of ALL animals in the region. Amongst other achievements, a number of significant arrests of some of the worst, most prolific long-term poachers in the region have at long last been engineered by Big Life's teams.

Thanks to the additional critically important support of the local communities, Big Life’s teams are now apprehending poachers almost every time they kill. As a result of these successes, Big Life has been able to quickly send out a strong message to poachers that killing wildlife now carries a far greater risk of being arrested.

But the aim of Big Life was always to do much more than just catch poachers. It was to protect the entire ecosystem, both in the short and long term. If the community is not on board, it is all for nothing. Significant resources go towards helping both the local communities and animals in the inevitable human/wildlife conflict that occurs on a constant basis, in the form of crop raiding and predator compensation for killed livestock.

September 2012: Maasailand Preservation Trust Merges With Big Life Foundation

In September 2012, the Maasailand Preservation Trust was folded into Big Life Foundation. This means that Big Life has significantly expanded both its resources and operations: it now employs hundreds of rangers across the entire ecosystem.

Big Life’s mandate has also expanded to more clearly foster and nurture the critically important relationship between the communities and the wildlife, supporting educational programs and constantly working with the local communities to ensure that protecting the wildlife is a winning situation for all, economically, ethically, and environmentally. For the people, the animals, and the planet.

Meanwhile, however, the destruction of wildlife continues unabated, escalating and out of control, in the areas beyond where Big Life and the likes of KWS still have no presence. When the goal of stable and sustainable operations long-term has been achieved in the Amboseli region, the goal is to then start allocating funds to expanding programs contiguously.

Big Life Rangers in new Land Cruisers, March 2011

Big Life Rangers in new Land Cruisers, March 2011