Click here to view the Safaritalk's interview with Nick Brandt June 12 2011.

-Amboseli-2007-Killed-by-Poachers-2009-(c)-Nick-Brandt-2011.jpg)

Elephant Drinking (Igor), Amboseli, 2007. Killed by Poachers, 2009. © Nick Brandt 2011

What are you doing that is different from the plethora of wildlife NGOs already operating in the field? Before Big Life, there were basically no wildlife NGO's concentrating on full-scale anti-poaching programs within the Amboseli ecosystem on either side of the border. Kenya Wildlife Service tried their best, but were completely underfunded, and Richard Bonham, who is now Director of Operations for Big Life, was severely underfunded in what he could achieve with the Amboseli Tsavo Game Scouts Association. So what we are doing - a well-funded comprehensive anti-poaching operation on both sides of the border within the ecosystem - is effectively a first. Considering the critical importance of the Amboseli ecosystem within the context of the wildlife of East Africa, I think what we are doing is critical. My belief is that to be truly effective, you need someone in charge right there on the ground, with the ability to direct and co-ordinate operations first hand, to work in close partnership with the Parks, the local communities, and with the other NGO’s, to marshal everyone’s resources for maximum efficiency for everyones’ benefit. With Richard Bonham as Big Life’s full-time Director of Operations in Africa, we have this. Richard has lived in the Amboseli area for decades, knows all of the key players there, and has a better understanding than anyone of how to address the multiple problems. Meanwhile, on the Tanzanian side, Damian Bell is Big Life’s Operations Manager in Tanzania. As founder of Honeyguide Foundation, he has an outstanding relationship with the local communities and wildlife departments, perhaps more so than anyone else in Northern Tanzania. On the Tanzanian side, there has been almost no-one to stop the poachers having free rein. And when poachers have come into Kenya from Tanzania to kill elephants before escaping back over the border, they have simply gotten away, because there was no cross-border anti-poaching team with which to communicate or co-ordinate. Now, two of our most significant arrests of poachers have been ones who escaped from Kenya into Tanzania and, through coordination of our Big Life teams in both countries, were able to arrest those poachers, poachers whom for as long as two decades had been systematically poaching Amboseli's wildlife whilst evading the authorities.

What is your answer to the following: Is all the money which is being donated to the various and numerous NGOs really making a difference, or would it be better spent funding a militarised force to provide 24/7 protection for wildlife in Africa? No, militarised personnel can only ever be one part of the solution.If you went solely that way, you'd never win. First and foremost, you have to have the support of the local communities. For example, realistically, even with patrol vehicles, our 100+ rangers so far cannot possibly begin to cover 2 million acres on their own. The way they are truly able to be effective is to rely on informers' information - most of the arrests of poachers come from information supplied by informers.

What assistance is the Kenyan and Tanzanian Governments and wildlife authorities offering to your initiative? So far, we have great support for our initiatives. Kenya Wildlife Service and Big Life are working closely together to great effect. KWS are going to be providing training for our rangers, supplying us with two armed rangers for each of our outposts, later in the year, and they have also promised to give some of our rangers Kenyan Police Reserve status, so that they can be armed. KWS completely appreciate our help in protecting the huge buffer zone areas around Amboseli. Further evidence of KWS's support is that when we had our official launch of one of the outposts, the Director of KWS and the Chairman of the Board both came for the opening. In Tanzania, our Operations Manager, Damian Bell, of our partners Honeyguide Foundation, is working closely and effectively with the Wildlife Division and the all-important village councils. At the Tanzanian launch, all three of the administrative regions in which we're working sent their most senior government people to pledge their support.

Problem animals and human vs. wildlife conflict. How will those you work with counter such problems, if such instances occur within your areas of operation? Human/wildlife conflict occurs constantly in our area due to the large amount of farmland in the Kilmanjaro foothills and on down from there. We devote a significant amount of ranger patrol time to these areas, where elephants raid the crops, etc. Thunder Flashes - a harmless noisy pyrotechnic - are used by our teams to scare off the elephants. These only work so much before the elephants come back, so constant vigilance is required. But since we put our rangers in patrolling, the number of elephants being speared and poisoned by farmers has dropped massively, which is very encouraging.

Subsistence poaching versus professional poaching syndicates. How do you deal with the two facets of poaching: and, what kind of poaching are you tackling? Solely ivory poaching, or the illegal bush meat trade as well? Do you, for instance, have a reward payment scheme that has been initiated for communities which don’t poison lions, or which go out and assist in snare removal for example? In my opinion, the single best use of donor money for wildlife protection, is money for a network of informers. We have vastly expanded the pre-existing network of informers, and greatly increased the rewards - up to $1500 for information leading to the arrest of someone caught with ivory. It was information from our informers that led to Big Life teams arresting of two of the worst, most prolific major poachers and their gangs in the Amboseli region, poachers who had been systematically poaching for the last two decades, and whom up until that point, the authorities had been unable to pin anything on. We are focused on ivory and illegal bush meat poaching. This isn't just limited to catching the poachers, but also catching the traders, and trying to follow through as much as we can on all prosecutions.

Where do you see the greatest threat to wildlife coming from in the Amboseli ecosystem, and what methods are you employing in order to combat it? Two, really : Obviously, the recent massive escalation in poaching for both commercial and bush meat; and the ongoing population pressure and loss of habitat, which obviously leads to human/wildlife conflict, in the form of spearing and poisoning, from elephants to lions, hyena and cheetah on down.

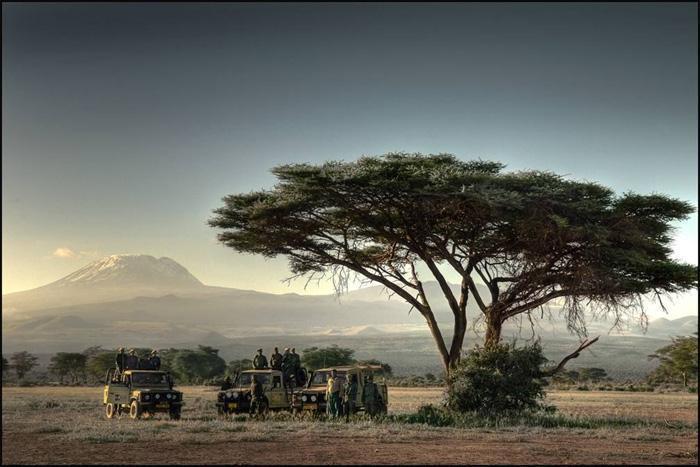

Big Life Rangers in Kenya, Jan 2011.

Other than the usual educational programmes, how do you integrate local communities into your efforts? Do you employ local people in positions of authority? 99% of our employees are local. The only non-locals are Richard and our Field Co-ordinator, Llewellyn DYER. We feel that it is essential to employ the local community - to engage them emotionally and economically in preserving the wildlife so they can se how they benefit. As an example, a month or so ago, a lion killed a cow of a village elder. The Masai warriors went on the hunt to kill it, but the village elder told them not to, as his son now worked as a Big Life ranger.

Fighting fire with fire. Following on from the recent report in www.theeastafrican.co.ke entitled “Militant groups fuel poaching in East Africa” are you prepared to place your scouts and wardens in mortal danger, and what will be their rules of engagement? What equipment, arms will they be supplied with in order to counter the well armed and trained criminal poaching syndicates? The rangers are aware of the risks of their job. Part of our responsibility is to train them for dangerous situations without putting themselves at undue risk. In fact, the Tananzian rangers wrote a song which they sang to us just this week, part of the lyric of which go something like this: "mother, I have a job as a ranger. If I die, don't cry for me, because I am doing it for conservation..." In terms of weapons, the Tanzanian rangers are getting their weapons in the next month, and in Kenya, the Director of Kenya Wildlife Service has promised us that our rangers will receive Kenya Police Reserve status by the end of the year. In the meantime, they work closely and effectively with Amboseli's KWS teams. They seem to appreciate the support we can give by protecting wildlife in the huge buffer zones around the park and are planning to put two armed rangers into each of our camps in a few months. And to help them, we have donated a new Landcruiser to their single armed Wildlife Protection Unit to help them implement their mission.

Big Life Rangers in Tanzania, April 2011.

At the recent International Conference on Biodiveristy, Land Use and Climate Change in Nairobi it was suggested that many of the problems with the future viability of the natural resources of Kenya (for instance) revolves around the lack of a cohesive central organisation to co-ordinate the many public - private partnerships in conservation, landowners, businesses etc. Noting your comment on your website “With particular emphasis on countering the recent alarming escalation of poaching of African wildlife, Big Life seeks to work together with other NGO's in the areas to consolidate, coordinate and collaborate on all information and resources, so that as a team, maximum efficiency and effectiveness for protection of the ecosystems can be realized.” Do you see the future of Big Life Foundation taking a proactive role in this wider area or are you satisfied if you can work in the Amboseli ecosystem and make change in that important area? In Amboseli, we are urgently acting to stabilise the situation. On the one hand, it grieves me that we are not addressing more than this one admittedly huge and critically important area, but I also know we should not move on to other areas in desperate need of help until the situation is stablised in Amboseli with an ongoing stable funding base. As and when we achieve that, I would want to direct funds elsewhere, but only using the same template that is working in Amboseli - with someone with intimate knowledge of the place and the people who lives there, running the project on the ground.

Also coming out of this conference were concerns regarding the new Kenyan Constitution and the effect that the two tier government will have on the abuse of natural resources. For instance, funding to county councils being reduced to such low levels that to survive they may have to exploit natural resources in their area to such an extent that survival of the wildlife is threatened even more. Now that you have a Foundation with the goal to ”help slow down and ultimately halt the further destruction of the natural world” do you see yourself becoming more political in the future? You pretty much have to get political. Not just locally, but also nationally and internationally. Locally, county councils are beginning to understand the economic benefit of wildlife and good environmental stewardship to their natural areas. Nationally, we need to do everything we can to persuade the government of the same - something that seems to be a problem with just abut every government on the planet with the exception of a few like Costa Rica. And internationally, we have to exert urgent pressure on the governments of the Far East to make far more efforts to enforce the illegal trade in animal parts. I wish I had more time to engage in the international aspect, to target the problem at its source, but there are only so many hours in the day. So in the meantime, I hope groups like Wild Aid continue their incredibly hard but important initiatives in China and the rest of the Far East, to educate the people there as to the terrible destruction being wrought in Africa as a result of their desires.

-Amboseli-July-2010-Killed-by-Poachers-August-2010-(c)-Nick-Brandt-2011.jpg)

Elephant with Half-Ear (Winston), Amboseli, July 2010. Killed by Poachers August 2010. © Nick Brandt 2011

What responsibility do you feel that frequent travellers to wildlife in Africa have to maintain the ecological future of the wilderness they love to visit? For instance, it has been suggested that tourists put more pressure on their guides to behave ethically; that they become better informed about the environmental credentials of the camps and operators they use; that they should be more responsible with how and where they spend their money and that they would be better served by donating more of their safari dollars to conservation and give up some of their visits. I absolutely wish that visitors on safaris would research the lodges and tour operators with environmental responsibility and make the effort to only go with these. There are some great, environmentally responsible lodges and operators out there, but there are also thousands who are anything but. If you go with the right operators, you know that some of that money going back into the local community and helping, directly or indirectly helping the local wildlife. You won't get that with the likes of a Somak who don't give a damn about anything other than a quick profit. For them it's just bums in beds, quantity rather than quality, at the expense of the environment, the animals, and of the local communities. For those operators and lodges that don't give a damn, they are being short-sighted not putting anything back - no-one will come if there are no animals left.

There is a lot of discussion on many forums regarding your methods of photography and post production. Do you feel that the added mystery provided by fellow photographers not being sure how you achieved your end result enhance the desirability of your images? I do get irritated at some peoples' certitude that some of my images could only have been engineered in Photoshop, when in actuality, they were the result of frigging weeks and weeks of endless waiting for all the right elements of animals, location and light to align. I almost feel like I have to release the more inferior, flawed frame just so it doesn't look so perfectly arranged, while that 'perfect' frame took me forever to get. There's also one effect I used to do that people are convinced is created in Photoshop, which is actually a physical impossibility, and is achieved all in camera in a very crude, simple way. I don't feel that the added mystery enhances the desirability of the images. I just don't see why everyone these days needs to know everything about how every technique is achieved by every photographer/filmmaker/musician/painter etc. Coca-Cola keeps its recipe secret. I keep some of mine, as I would expect many other artists to do. All you need to know about my photos is that what is in the final print maintains the integrity of what was actually there at that moment in time - those animals, in that place, under that sky.

What do you say, if anything, to the professional wildlife photographers who turn up their noses at any photography of wildlife that isn’t a totally realistic depiction of the scene in front of them? Not comparing myself, but just as an analogy, it's equivalent to a landscape photographer turning up their noses at Ansel Adams or Edward Weston. For them, the negative was just the first step towards the final image. I am not personally interested in taking purely documentative photography. I want it to be interpretative, subjective, personal. My final prints do maintain the integrity of what was there in front of me at the time - those animals in that landscape under that sky were all there. But the grading of the image, the burning and dodging of the image is often very detailed. I do however think that I over-worked my photos in the early years - in a way that embarrasses me now, and ironically, it's the most crude, worst aspects of that early work that I see most copied. The grading is much more subtle now.

Given this resistance to a more artistic approach to showing wildlife, what advice would you give to a new photographer who wants to pursue a career as a wildlife photographer but not in a traditional manner? I do not in any way consider myself a wildlife photographer. A wildlife photographer photographs a more documentative view of the world, usually attempting to shoot animals in moments of high action. I am much more interested in capturing animals simply in the state of Being, as sentient beings not so different from us, living within an astonishing natural world that is disappearing fast. And as will eventually be more clearly revealed in the third part of the trilogy of books, showing the way they and the natural world they inhabit are being destroyed. But I really have no particular advice to any photographer, other than always photograph for yourself, never for others. But that applies to any artist in any art form.

It seems to be a great and logical fit that a photographer who is able to show a more sympathetic, aesthetic and soulful view of wildlife would, as a consequence, want to preserve that wildlife. Is this in part, why you formed Big Life Foundation? Initially, when it was first suggested by a few people that I start my own Foundation, it seemed to me like a very self-aggrandizing and self-important concept, which made me extremely resistant to the notion. But I began to realise a few things : when it came to Amboseli, money for wildlife protection was in dangerously short supply, and that, through virtue of the audience for my work, and some wealthy collectors of the prints, I had access to potential major donors in a significant way. Of course, that means nothing if you can't back it up with serious ideas and intent. And so far, that has proven to be the case.

Are you planning to inject personal funds into Big Life Foundation, or are you using your profile to encourage others to provide the funding required? This leads into the question - why should we donate and support your foundation over others? I've injected a lot of personal funds to help get the ball rolling, about 10% of our raised funds. I was fortunate enough to have two of the best collectors of my work, Fiona Druckenmiller and Stan & Kristine Baty, inject a combined $700,000 so far into Big Life. We really owe Big Life's existence to Fiona's fantastic initial generosity, and faith in my intentions before anything had been proven. Why should people donate to Big Life over others? With no internal bureaucracy, with Big Life's Director of Operations, Richard Bonham, being right there on the ground, donor money goes where it needs to go, and it goes there fast, efficiently and effectively. We don't hang around. We can't afford to. That's why within just a few months, the poaching in Amboseli has been significantly reduced, and some major, prolific long-term poachers finally arrested. We are also working in a unique area where there was next to no protection, which was crazy considering Amboseli has, in my opinion, the finest elephant population in East Africa. The template, the methodology we are applying is working very well, and if we receive enough money to the point where our operations are sustainable and stable in the Amboseli ecosystem, we can then apply that to other areas in East Africa in critical need of help.

-Killed-by-Poachers-2009-(c)-Nick-Brandt-2011.jpg)

Elephants Walking Through Grass, Amboseli 2008. Leading Matriarch (Marianna). Killed By Poachers, 2009. © Nick Brandt 2011

In fifty years time, how did you see the state of African wildlife? Well, in the space of far fewer years than that, at the current rate of destruction, there will be no animal populations of any consequence left outside unprotected areas. It's already happening at shocking speed. Where there are animals, those areas will have to be protected, not just under the guise of official Parks and Reserves, but also through concession areas, and large buffer zones to Parks like we are protecting in the Amboseli ecosystem. I also think there will be more fenced-in glorified giant zoological parks like Lake Nakuru in Kenya. Of course these cannot accommodate migratory animals, or sustain a species like elephants who plough through an enormous amount of vegetation daily.

However, constant vigilance will have to be maintained. Local communities will hopefully see more and more the value of preserving the wildlife for their local economy, but it always only needs a few bad seeds, be it corrupt government or external militia looking to make a fast profit, to destroy those precious remaining areas in a nano-second. Add into the mix both climate change from a combination of deforestation and global warming, and the ongoing pressure from a fast-growing population, and the resultant pressure on diminishing natural resources, will make it even harder to maintain even those protected areas.

However, I would not be devoting the enormous amount of time and energy to preserving this stunning world if I did not think that we stood a chance of preserving certain critical areas like the Amboseli ecosystem (but then I think every natural area is critical, and I just wish that we had enough money to protect all of them starting NOW).