By Tom Hill

Images: Lisa La Pointe

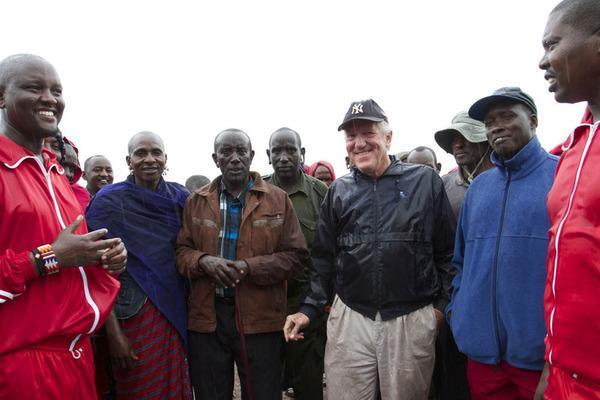

Under threatening skies, a first-of-its-kind track and field event between two rival Maasai warrior villages was held this day. The competition took place on a primary school sports ground just outside Rombo town in Kenya’s Amboseli-Tsavo ecosystem, at the very foot of Mt. Kilimanjaro. It was the first of a series of six regional track and field competitions to be held in coming weeks, all building toward the Maasai Olympics, a one-day sports celebration for the warriors of the entire ecosystem to be held on December 22nd.

For the first time in their long and noble history, two neighboring “teams” of Maasai warriors competed against one another not over how many lions they could each kill but over how many track and field events they could each win.

The idea behind the Maasai Olympics is to provide these young warriors an alternative way, a far more acceptable and sustainable way, to prove their skills, identify their leaders, and attract girlfriends. Only time will tell whether this day was indeed a tipping point in the attempt by Maasai leaders here to remove lion hunting from the culture itself -- even declaring it a cultural taboo.

But what was certain, well before the event had concluded, was its immediate success and acceptance by the warrior athletes and the families and friends who came to cheer and encourage their favorite participants. The atmosphere was unmistakably that of a joyous sporting event being held in front of true fans, just like anywhere else in the world.

And even before the competition began the symbolism of great change was in the air. Iltuati age-set warriors wearing their iconic red shukas and traditional jewelry, literally from head to foot, were seen laying down their spears and picking up instead handfuls of white ash. These young men had volunteered to mark off the lanes of the running track, a 400-meter oval, sifting the white ash carefully through their fingers inches from the ground as they moved slowly around the sports ground.

The lanes had been laid out the previous day by Maasai Olympics officials, led by project coordinator Samuel Kaanki, using an inexpensive tape measure, scratching straight – if sometimes a bit wobbly – lines into the hard barren dirt of the sports ground using a stick. Once the warriors had completed their task, the final result was more than satisfactory, the symbolism of the scene somewhat breathtaking to consider.

Once a Christian prayer had been given over the public address system borrowed from a local church, the first two events were to get underway simultaneously: javelin throwing for distance and rungu throwing for accuracy (the rungu is a wooden device used as a small weapon by livestock herders, thrown end-over-end).

The two areas set aside for these activities fit comfortably within the oval of the track, allowing spectators to stand on either side of each venue and watch the action in both directions.

“Competitor number one, first attempt!” shouted Joseph Ntoipo, a government chief and Maasai Olympics official, standing at the throwing line for the javelin. Samar Ntalamia, programs manager for the Big Life Foundation, whose job would be to measure the distance of each javelin throw and record it in a spiral bound notebook, stood some 50 meters away and signaled back that he was ready.

The first regional event of the first-ever Maasai Olympics was underway!

The order in which the five competitors from each manyatta threw the javelin or the rungu had been determined by a random draw – each boy pulling a soda bottle cap out of a hat. The bottle caps had been numbered from one to ten with a felt-tip marker.

As the first competitor prepared to throw the javelin, the other nine stood together just off to the side, watching intently, not moving nor making a sound. A notable tension could be felt on the rise...

The first competitor’s face showed the classic focus of an athlete in the process of competing – eyes staring far down the throwing ground where he was envisioning his javelin landing, trying to stay loose, rolling his shoulders, shuffling his feet, twisting the javelin nervously in his throwing hand.

Then he was off . . . measuring and pacing the steps of his approach to the throwing line so as to release the javelin with maximum velocity as close to the line as possible without stepping over and nullifying his throw.

Good javelin throws were met with oohs and aahs from the fans and vigorous clapping, not so good throws received respectful silence. Teammates celebrated a good throw by exchanging high-fives and even the most contemporary gesture: fist bumps.

David Lairumbe of Rombo won the javelin throw, after three efforts from each competitor, with a toss into the wind of 45 meters. Rombo swept the javelin competition, gaining all six points – three for first, two for second, and one for third.

The rungu event was won with a score of 4 points by Saruni Mwanta of Kuku who hit the target most frequently and most centrally in his three attempts. Kuku also placed second, while a Rombo warrior finished third. The team score now stood at 7-5 in favor of Rombo.

Next up was the 200-meter run. The runners were assembled by one official at the precise point on the oval track that would take them around an initial curve then onto a straightaway to the finish line: a piece of string held waist-high by two officials. Three other officials, each with a stopwatch, were at the finish line as well, one charged with recording the precise time of the first runner to cross the line, another for the second finisher, and one more for third. This method would insure, even without the benefit of fancy electronic devices or video replay, that there would be no dispute as to who won the three cash prizes to be awarded at the conclusion of the overall competition . . . and no arguments or disputes arose throughout the entire competition for any event.

The 200-meters was won by Nelson Kayian of Rombo in a time of 26.05 seconds. As he crossed the finish line, less than a half-second ahead of his closest pursuer, friends rushed onto the track to grab him in celebration. Rombo also finished second in the 200-meters and their lead now widened to 12-6 over the Kuku warriors.

The 5,000-meter run was next. By this time a considerable number of additional women had arrived, some older -- very possibly mothers of the athletes and their friends -- and some the age of the warriors, each woman in full traditional dress, wearing every item of jewelry they each possessed. The colorfulness and beauty of the crowd had increased quite dramatically.

After a staggered start, the long-distance runners moved to the inside of the track and began their journey of twelve and a half laps around the oval. Each time the runners came by the fans, sheltering in the shade of trees near the finish line, there was an outburst of shouted encouragement and applause. One woman, who was supporting the runner who eventually won, could not contain her enthusiasm, and would run out, nearly onto the track, and jump with joy, throw her arms high in the air, and run along with her guy for 15 or 20 meters, then return to the shade of the trees until his next time around the track.

This runner, Jacob Parmuya of Rombo, was the class of the field this day. His long and steady stride had a rhythm like no other runner, his pace never slackened and he moved progressively away from the next closest runner and even lapped several of the slowest runners, meaning he was well more than 400 meters ahead of them when he took the tape. To their credit, even after the winner had concluded his race, the slowest competitors continued around the track one more time to complete theirs. The winning time was 15 minutes 29 seconds.

Kuku grabbed second and third place in the 5k but the score now stood at 15-9 and Rombo only needed a third place finish in the final event to clinch victory.

And the last event event, but certainly not the least event, was high jumping. This is not Olympics style jumping, where the competitor runs up to and then attempts to leap over a bar on his back; this is vertical jumping from a standing position – Maasai-style -- more like the vertical leap required for a jump shot in basketball.

The device made by the officials to measure the winning jump – defined as the jumper whose head reaches the highest point from the ground (obviously favoring the taller competitors) – was constructed from a few pieces of thin raw lumber, a handful of nails set at six inch intervals going up from eight feet to ten, and a piece of string suspended on the nails, connecting the two support poles. The competitors were attempting to touch the string with the tops of their heads and, if successful, they moved on to a higher setting until only one jumper had touched the string at that height.

To move the string from one height to another without having to take the poles down, a branch had been gathered from a nearby tree and a grove chopped into one end with a Maasai panga, allowing a man of normal height to move the string to a height of ten feet with ease. To keep the string taut, so no competitor would have the advantage of a sudden sag caused by the wind, it was tied on both ends to rocks that dangled down freely, insuring the string remained taut at all times.

As the high jump event was about to begin, the crowd in its entirety surged out to the center of the oval, surrounding the poles in a large circle. The competitors and officials were lost somewhere in the center of this highly energized crush of humanity.

As expected, the warriors began to sing as the competitors began to jump. Maasai warriors cannot jump traditionally without singing and this event proved to be no different.

What was particularly noteworthy was all the warriors were singing for all the competitors, not supporting just their own teammates. The bond of warriorhood culture had overridden the division otherwise created by the sporting competition between their villages. This moment, more than any other, with the spectators at their highest level of excitement as well, seemed to reflect the spirit of the entire day, the sense of an ancient brotherhood evolving a new spirit for competitive athletics... and most definitely doing so in Maasai-style. In the western world, this simply would not have happened.

Perhaps someday it won’t happen here either but – on this day and only this day – a sporting competition of this scale, and the behavior appropriate for it, was something as new as it could possibly be and would never be again.

The winner of the high jump was Metui Kayiok of Rombo at a height of 9 feet 5 inches. Rombo also took second and the final score was a convincing 20-10 win for Rombo.

“That finishes the competitions!” shouted Daniel Sambu, an Olympics official and manager of the Predator Compensation Fund, over the den of cheers and laughter that had accompanied Kayiok’s last jump, one so spectacular that he “played” with the string -- as if he were suspended in mid-air -- touching it more than once by arching his neck back and forth at the top of his ascent in the signature way only the Maasai people can do.

One minute later the sky opened up and the rain began to fall. People scattered for cover and the sports ground turned into a quagmire. After forty-five minutes the rain slackened and about half of the crowd re-appeared and formed a circle, standing in mud up to their ankles, grinning at one another through the raindrops, unable to constrain their collective joy; the white ash lines of the track now but a precious memory.

The winning athletes were introduced one-by-one and handed their cash prizes: 10,000 Kenya shillings for first, 7,500 for second, and 5,000 for third.

In my brief remarks, beyond thanking all of those who made the event possible and those athletes who participated with such determination and enthusiasm, I said, “My understanding of Maasai culture is that rain is the manifestation of a blessing.” Everyone smiled and nodded in agreement. “Therefore I think it is safe to say this event and this hopeful new age of Maasai warriorhood has been blessed.”

The chairman of Rombo Group Ranch followed me and concluded the day’s events by saying, “Somehow this event – for the first time -- has channeled the youthful energy of our warriors from lion hunting to trophy hunting.”

Next up is Mbirikani versus Ogulului.