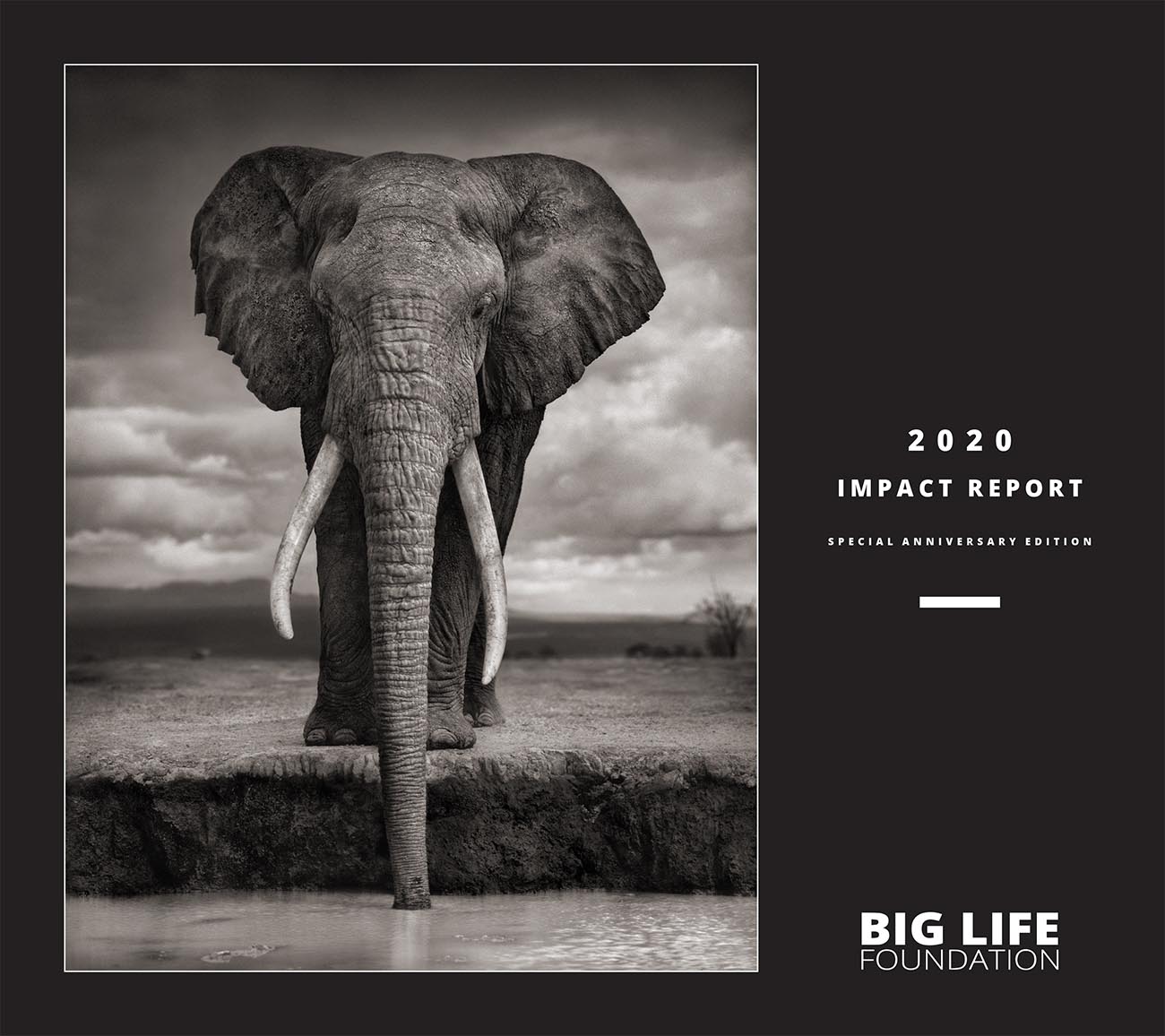

His name was Igor.

For 49 years, he wandered the plains and woodlands of the Amboseli ecosystem, so relaxed that in 2007, he allowed me to come within a few meters of him to take his portrait.

Two years later, in October 2009, he was killed by poachers for his ivory.

At that time, on an almost weekly basis, many of Igor’s brethren were being killed in the same way. The Amboseli ecosystem, with one of the most important populations of elephants left in East Africa, was suffering badly due to insufficient funding of both government and the very few nonprofit organizations in the area.

Action had to be taken, and urgently, to fill the gaping hole. I had a series of plans, among which were:

- A local leader on the ground to direct and coordinate operations firsthand, to have an open door and an open ear to the local community. If you don't have the local community on your side, you're screwed. For exchange of information, the bush network beats the social network any day.

- Teams of rangers that were locally hired and fully mobile, with vehicles, radios, and tracker dogs on stand-by. All obvious stuff.

- Cross-border anti-poaching patrols. Most of the poachers were coming over the border from Tanzania, making their kills, and then escaping back with no-one to arrest them on the other side. Teams of rangers on both sides of the borders were needed, working in close communication, to track and pick up any poachers escaping back over into Tanzania. No organization had yet done this, but animals don’t pay attention to borders, nor do poachers, so neither should we.

Back in the US, I visited a collector of my photos and talked her through my plans. She immediately committed $500,000 a year for the first 3 years. We will be forever grateful to that donor (who prefers to remain anonymous). In that one moment, with that money, things became possible.

I had a name: Big Life Foundation. Now I needed that leader on the ground.

There was one renowned conservationist with a great reputation who lived in the Chyulu Hills.

His name was, of course, Richard Bonham.

For 20 years, Richard had been building an effective conservation force in the Chyulu Hills with his Maasailand Preservation Trust. Richard had the same holistic vision of conservation - community rangers, support of the local community, a livestock compensation fund, and more.

I wrote to Richard about my plans and asked him if he knew of anyone to run Big Life. He wrote back that my plans were what he had been shouting from the treetops for years, but had never had the funds to implement. To my surprise and delight, he suggested that he could run Big Life. This was the perfect solution - someone with his reputation and 20 years of experience, running the organization on the ground.

In late 2010, Big Life fired up and went into action with Richard as its co-founder. Igor became Big Life’s unfortunate poster child, and his home, the Greater Amboseli ecosystem, is the place where Big Life today protects 1.6 million acres.

With that first precious funding and subsequent donations, within a year, Big Life was able to hire 85 fully-equipped well-trained rangers plus platoon commanders, construct 12 anti-poaching outposts, purchase 9 anti-poaching patrol vehicles and a Microlight plane for aerial monitoring, and grow an informer network on both sides of the border.

A series of quick dramatic arrests was made of several major poaching gangs, who had been poaching the Amboseli region's elephants for many years. They were tracked down by Big Life’s teams in exactly the way we had planned, through coordination between rangers in both countries, our network of informers, and local community help.

Cut forward to the present day.

Under the stellar, rock-solid leadership of Richard and now also his second-in-command, Craig Millar, Big Life has become the biggest employer in the region, with 500+ local staff.

And so it is that 10 years on…

The number of elephants killed by poachers last year in the areas patrolled by Big Life rangers was ZERO. The number of rhinos killed by poachers last year was ZERO. The populations of elephants, lions, giraffes, cheetahs, and most other species in the ecosystem have all markedly increased since 2010.

However a new threat to elephants was growing in the ecosystem. More elephants were now being killed by farmers whose crops had been destroyed than by poachers. Only a few years ago, 20 elephants were killed in one year in this way. To solve this latest problem, Big Life built over 100 km of electrified fence. As a result, in 2020, just two elephants were killed. And now, because of this, both elephants and farmers live happier, safer lives.

But now, we face the biggest, most complex threat of all.

And it all comes down to land.

Back in 2010, to combat the poaching, to staunch the flow of blood, we were engaged in a form of triage. By triage, I mean that we had to make brutally hard decisions about which were the most critical areas to set up outposts, knowing that we were leaving many elephants in other areas unprotected until we got more funding.

Today, we find ourselves dealing with another utterly necessary form of triage: to save the most important land for wildlife through leasing wildlife habitat before it is swallowed up to development.

The ecosystem is being rapidly transformed from community-owned land into private ownership that will shatter the landscape into thousands of 20-60 acre parcels. As the parcels are converted to other uses, wildlife will run out of space. It will be difficult to preserve the ecosystem in its current state. However, there are key wildlife corridors and dispersal areas that we can still protect, which would allow the ecosystem to support wildlife numbers similar to those now.

Today, this is Big Life’s most urgent task. There is no time to waste. Land preservation can be a win-win for all, not just for the animals, but also for the local communities.

Thank you to all of you from me, Richard and everyone at Big Life for being with us on our journey up until now.

We hope that you will stay with us for the next, most vital stage of our journey.

Nick Brandt

Read the Full 2020 Impact Report.